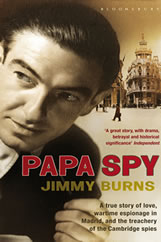

I was in Dublin last weekend, talking about my latest book Papa Spy at the Cervantes Institute, in an event jointly organised , and charmingly so, by the Hispanic department at Trinity College with a helping hand from former FT colleague Manchester-based Alice Owen, who works as a free-lance publicist. There was a great turn-out of new fans and old friends, led by author and former Irish Times journalist Paddy Woodworth, who knows a fair bit about Spanish culture and history and generously agreed to be ‘in conversation’ with me.

Of the promo gigs |I have done over the last few months, this one was the one that elicited the warmest welcome and proved the most worthwhile. My hosts showed themselves pleasantly surprised and grateful that I had made the effort to include Dublin on a staggered tour that has focused on England, Spain, and the east coast of the US. They reciprocated by ensuring a good turn-out. Local bookshops made a herculean effort, despite the snow-provoked chaos in distribution, to stock copies not just of Papa Spy, but also two other books of mine, Barca and Hand of God. A lovely and energetic local rep from my publishers helped things along. I was put up at the Trinity Capital, a wonderfully esoteric, chill-out hotel on the site of a former British army recruiting office where you go to sleep and wake in a state of glowing well being. This was Ireland and its people at their Celtic best.

Over at the nearby Cervantes Institute, my Irish audience was genuinely interested in my book. Espionage, deception, dirty tricks, Catholicism, and wartime neutrality are themes that form part as much of their history, as it does that of Spain in WW2 where my father, the spook of the title, lived and worked and eventually married my Spanish mother, with some help along the way from an Irishman.

It was an honour to have the journalist and historian Charles Lysaght among my guests. The biographer of the newspaper baron and wartime propaganda chief Brendan Bracken, has studied closely the inner working s of the wartime British Ministry of Information. Lysaght pointed out that Bracken had always thought it a good idea to have as many foreign correspondents as possible reporting on wartime England as part of the Allied propaganda effort. So did my father, the British embassy’s MoI recruit, although one or two or the Spanish journalists he sent to England were suspected of being Nazi agents, as the head of MI6’s Iberian section Kim Philby was the first to point out. When questioned on this by Paddy Woodworth, I pointed out that Philby hated my father for being pro-Francoist and a Catholic. Philby was also a Soviet spy. Of this there can be no doubt.

Lysaght however insisted that it was not true, as he suggests in his biography (and I report in Papa Spy) , that Walter Starkie, the Irish Trinity College professor , had met with Bracken in Dublin on the eve of war and may have provided some interesting information about those Irish opposed to the Allied war effort.

I was on firmer ground talking with Paddy Woodworth about Starkie’s close links with my father as wartime head of the British Council in Madrid. The Spaniards nicknamed Burns and Starkie, Quixote and Sancho Panza, respectively, on account of their wartime adventures and contrasting physiques. While my father tried his best as an amateur spy and propagandist, earning a reputation as a womaniser along the way, Starkie proved a courageous, if somewhat eccentric British agent. Starkie liked playing Irish jigs, flamenco, and Spanish wine when not doing his bit for King & Country. The Irishman helped Jewish refugees and POW’s escape through Gibraltar and Lisbon, and organised a propaganda tour by the actor Lesley Howard, another British agent. Starkie was as virulently opposed to Irish neutrality, as he was passionately in favour of keeping Franco ‘on side’ during the war.

After engaging with my audience on Starkie, I moved on briefly to the subject of declassified documents held by Ireland’s Department of External Affairs. One showed that an IRA man who was held in prison by Franco after fighting for the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War subsequently joined the German secret service and went back to Ireland in a U-boat. “British propaganda!” someone from the audience cried. I thought it best to move on.

Later that evening, a group of Trinity College Hispanic academics kindly invited me to dine at a nearby Italian restaurant. Other Dublin friends joined in for some genial crack. Inevitably there was talk of how the cuts were already hitting departments at Trinity, just like almost everything else in Ireland. I shared anecdotal evidence of a new Diaspora: English hospitals are once again filled with Irish nurses. It was the first of a series of conversations I was to have over the next 48 hours during which the common denominator was one of a sense of deepening crisis, only salvaged by that very Irish sense that they had been in a far worse place before, and survived.

Over a late night drink at the Trinity Inn, Paddy Woodworth asked me a question that he had held over from the talk. How could I reconcile my father’s ‘cradle Catholicism’ with his evident lack of chastity in later life? I didn’t really have an answer beyond appealing to some modern theological justification of the Godliness that can lie behind varying expressions of sexual love. Paddy, brought up as a Protestant, has, like so many other Irish men and women-regardless of their faith- been both shocked and angered by the sexual abuse scandal of his the Catholic Church in Ireland, and the hypocricy, not to mention betrayal, that has been exposed. I left him somewhat mystified by the suggestion that the mystery of transubstantiation made it impossible for me to explain, still less defend, my enduring faith, rationally.

By contrast there were no shortage of Irish friends trying to make sense of the political and economic mess which their country finds itself in. Over a lunch of soup and coffee at the cafeteria of Dublin’s National Gallery, I caught up with the hugely talented actor Ardal O’Hanlon. I have been a fan of his ever since he played a goofy young priest in the excellent Fr Ted series, and have forged a friendship in recent times through football. We had not seen each other since working together some three years ago on an incisive and very funny TV documentary he wrote and starred in on the rivalry between FC Barcelona and Real Madrid. Ardal is a Barca fan and said he had much enjoyed taking his young son to the Nou Camp on his first time visit a few months earlier.

Ardal has just completed a hectic stand-up comedy tour of the UK. We had met on the flight over from Heathrow, he looking rather worse for wear. He blamed it on a charity show he had put on the previous evening to help pay for poor Irish citizens based in England who wish to go home and visit their families. This charity will bvecome an increasingly worthy cause as the Irish Diaspora inevitably grows again.

Like most comedians, Ardal is an intensely private person off stage, both thoughtful and intelligent and far from brash or outspoken.He admits to having to go beyond himself on stage although he acts with a concience. As he told me, on his recent tour he treaded carefully on the issue of sexual abuse, trying to ensure that his gags never descended into hurtful bad taste. He did some political gags, but not too many. While refusing to be tagged as political –both his father and grandfather were deeply involved in the politics of the Irish state-Ardal is a keen observer of the ordinary daily grind of life. He doesn’t believe believe in the coming of a Second Republic. Nor does he want it. If Ireland were to have a socialist revolution, he would be the first to pack his bags and head across the water. Ardal would like to believe that things are not as bad as people say. Instead he tells me he would be happy enough if Ireland simply went back to being what it had become, when he went to university, some twenty years back, PreCeltic Tiger, a small but growing economy in Europe.

Looked at in this way, the crisis is not insurmountable. While a majority of Irish people will probably never be as rich as a few Irishman became in recent years, there will not be another famine, nor will there be another Easter uprising or Civil War. What is needed is some well managed inward investment, and a world recovery-led export drive. But it’s is a big IF. Two friends familiar with Ireland’s financial sector I met separately questioned whether the current IMF-led austerity budget had a hope in hell of sticking with a general election just round the corner which will see the total humiliation of the governing partners, and a resurgence of socialist politics, south of the border, as most radically epitomised in the polling booth and on the street, by Sinn Fein. These same friends however argued, interestingly enough, that the crisis in the South makes it more difficult for the nationalist agenda to make progress in the North.

Back in Dublin city centre, the tourist shops still sell Leprechauns with their bags filled with coins and the legend, ‘The Luck of the Irish’. Local bookshops still give prominence to books on Irish politics and history, from pop-ups on the Easter Rising to heavier tomes on the IRA. And in the National Gallery, one of the most striking paintings I saw on the morning I met Ardal O’Hanlon, is one by one of Ireland’s leading 20th century artists showing a group of Irish peasants stripping off their clothes as they are preached to by their priest at a Holy Well. It was painted a time when the Irish poor were seemingly so gullible that they did anything their Church told them. That is no longer guaranteed these days.

These images lingered with me as I made my way to the Shelbourne Hotel to meet another old friend. Dublin’s best known Hotel, like the country’s best known bank, has been taken over by the state to save it from bankruptcy. In the run-up to Christmas, it was packed with party goers, from North and south of the border, trays of mince pies laid out in the corridors , and its legendary bar, still the watering hole it has always been for those wishing to flirt, or share information.

My friend was an old source from FT days- well versed in the politics of Ireland-north and south and insightful. He suggested that the Irish regulatory authorities were trying their best to put the house in order after the wreck provoked by the rotten apples, but it was an uphill task for a country that has seemingly surrendered control over its own destiny in a situation of political uncertainty. Ireland’s best hope was in forming an alliance with Portugal, Spain, Italy, and Greece and negotiating better terms from the rest of the world.

Two days in a capital city as small and intimate as Dublin can be revealing and I am not just talking here about the visible signs of accelerating poverty on the streets. Most people I talked to were of the opinion that things could not go on as they are, without something breaking. The question no one could answer with any certainty was exactly when or how things might break and what would come afterwards. It took the people of Dublin thirty years to decide what to replace Nelson’s Column with, after it had been blown by the IRA. An elected Irish government opted eventually for a modern spire symbolising hope in the future. One gets a feeling that things will unravel not just in Ireland but elsewhere in Europe in a much shorter time than that. I’m talking months not years. The Irish deserve all the luck in the world.

Comments