Swiss theologian Hans Küng died on Tuesday at the age of 93 in his home in Tübingen, Germany

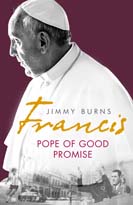

It was a real godsend to be able to see him and talk to him seven years ago when I was researching Pope of Good Promise and when his mind and body was still with him. It was the first and last time I met him and what a privilege it was to be with him. He was a prophet for the Church in our time !

This was my account of the memorable encounter as published in The Tablet in February 2014 and later in Pope of Good Promise.

The most telling evidence, for Hans Küng, that he has come in from the cold are three cordial letters he has received from Pope Francis. Küng shows me the latest, in which Francis says he has read an article by the Swiss theologian determinadamente – (“very carefully”) and that he welcomes the ongoing correspondence. “La carta y el artículo me hizieron bien” (“The letter and the article made me feel good.”)

In the article he sent to the Pope, Küng enthuses over Francis’ apostolic exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, while criticising the prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF), Cardinal-designate Gerhard Müller, for his insistence that remarried divorced Catholics are barred from Communion. “Determinadamente”, Küng repeats the word, after I have read out the full letter in Spanish. “This is important,” he says with similar emphasis. In that moment the old man seems to have the look of a rebellious student who after years of feeling unfairly reprimanded by a bullying teacher had finally earned his brownie points.

I meet Küng in a medium-sized house on a hill above the centre of the University of Tübingen, south-western Germany, that doubles as his home and the offices of the Global Ethic Foundation, which he helps run. It is our first meeting, and the figure who greets me with a warm handshake and engaging smile is frailer than the Küng of official photographs printed in his foundation’s leaflets or the sculpted bust on his lawn. In March, Küng will be 86, just a year younger than the also retired Pope Benedict XVI, whom he has known from when they were fellow professors at Tübingen in the early 1960s.

As I pass along a corridor and up the staircase leading to Küng’s study, I notice bound copies of Concilium, the international review of theology that my late father, the Catholic publisher and one-time editor of The Tablet Tom Burns, had helped give birth to over five decades ago. The likes of Küng, Karl Rahner and Henri de Lubac were heavily involved and subsequently active participants in the great renaissance of Vatican II.

I have come to talk with Küng about Pope Francis. Was he now more hopeful about the future of the Church? I ask. Küng replies: “This Argentinian Pope started immediately with a new style. With his direct language, with his simplicity. He showed himself human by asking people to pray for him.”

The Pope’s decision to shift his lodgings and main meeting place to the Domus Sanctae Marthae is consciously strategic as well as symbolic, he believes. Some things have changed, more than others, he continues. He notes, disapprovingly, that Archbishop Georg Gänswein, prefect of the papal household, is still Pope Benedict’s private secretary, and that the current prefect of the CDF is Müller, whom he calls a “professor of old dogmatics”.

Küng tells me: “Of course there are people in the Vatican now who are in a state of fear, of silent opposition. The question is whether the Pope will be able to overcome this opposition. A lot of things are going on in Rome which for me are indications that Francis wants to shake things up.”

He is heartened by moves towards greater accountability in the Institute for the Works of Religion, the so-called Vatican bank, and other well publicised changes – such as the replacement of former Secretary of State Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone and the removal of Cardinal Raymond Burke from the Congregation for Bishops – shows Pope Francis’ potential to be decisive and reformist. He is also hopeful that the Synod of Bishops will lead to changes he has long called for in church teaching on issues ranging from artificial contraception to the access to Communion of remarried divorced Catholics.

But for Küng, the most pertinent sign of the Pope’s “theological openness” is the personal correspondence he has had with Francis in recent months. This began when early in the new papacy, Küng sent Francis a copy of his new book and a letter congratulating him on his appointment of a group of eight cardinals from all continents with the mandate to initiate reform of the Roman Curia. Küng recounts in the preface to the English edition that he received, within days, a “personal fraternal handwritten letter in which he promised to read the book”. And so began the correspondence which has given Küng cause for so much hope.

“The first thing is that he is writing to me – a person that the CDF has declared is not a Catholic theologian. They tried to eliminate me spiritually. But now I have written to the Pope and I have received an answer immediately.”

In 1978, Küng locked horns with John Paul II over his criticism of the growing authoritarianism in Rome. In 1975, the CDF had asked Küng not to repeat his questioning of papal infallibility. But in 1978 he did so, in an introduction he wrote to a book by August Bernhard Hasler, How the Pope Became Infallible. Then in October 1979, he drew up a highly critical balance sheet assessing the first year of John Paul II’s papacy, which was published internationally as an article. In December 1979, the Vatican and the German bishops’ conference withdrew his mandate to teach as a Catholic theologian. And yet despite that attempt to silence him, Küng was allowed by the German university authorities to retain his chair of theology at the University of Tübingen, although the institute he presided over was separated.

from the Catholic theological faculty.

So would he like to be accepted again after all these years? “Well it would be nice. But they will have to do it very soon because I will not live very long,” he replies.

As he revealed in the volume of his memoirs published in German, but as yet unpublished in English, Küng has been diagnosed with Parkinson’s, and separately with macular degeneration which can lead eventually to blindness. He also suffers from polyarthritis in his hands which makes writing by hand increasingly difficult. Küng makes no secret of the fact that he is contemplating assisted dying in neighbouring Switzerland.

“How can you say that, as a Catholic? Surely life is a gift from God?” I ask him. “Yes, my life is a gift. But God also gave me responsibility for this gift. And I am myself responsible for what happens with me,” he argues back.

Küng goes on, with what seems a last burst of lucid mental effort at the end of a long day. “There are thousands and thousands of people who have dementia. One of my closest colleagues who lived round the corner died after suffering it for six years. I observed him. I don’t want to go through the same experience, and spend the last decade of my life like our great poet Johann Christian Friedrich Hölderlin, walking through this city being ridiculed by children … It doesn’t have to be injected. I can drink it; I can do it like Socrates.”

After a long pause, I press the question, more as a desperate plea: “But it is suicide – is it not?”

“Yes, it is suicide. But it is not murder. It’s giving back my life to my creator … My position is very different from people who do not believe in eternal life and who think only of nothingness. I hope to come back to God, back to my origins. I am in his hands.”

Küng is not alone in believing that modern demographics and the advance of medical research have opened up a necessary new area of theological debate about assisted dying, as it has far longer been around in the area of artificial contraception and abortion.

“It’s like the problem of birth and the origin of the human being. The Church’s official teaching is that it is the will of God that you are not to have contraception. Now they are saying it’s against the will of God to help you die. The fact is that birth and dying are our own responsibility.”

Küng acknowledges that this is a position that is difficult for me “as a friend” to understand. I tell him that it was not the only difficulty I face. His latest book dismisses the counter-Reformation as a dark age. It also makes no concessions to mysticism or questions the validity of forms of popular religion of which Pope Francis has spoken favourably.

He replies that Anglicanism has “done a few things very well”, including a vernacular language and having elected bishops (except in England itself ), that he is against superstition and complete decentralisation, and wants priests as well as laity in parish life. He supports the papacy as a pastoral Petrine office within the Catholic Church, but takes the Gospel as his yardstick for reform. “I think Pope Francis is a Pope of the Gospel.”

And so we end where we began. However, I remain saddened by some of the things I’ve read and by things we have talked about. The Küng, respected by his followers as a courageous prophet seems, once again, to be pushing the boundaries of his theology to a position that many Catholics will see as an attack on their faith. And yet his lifelong dedication to the cause of reform and renovation within the structures and for changes to some of the other teachings of the Catholic Church seems to resonate with my hopes for the Francis papacy.

Before I leave, I tell Küng I still consider him a priest and ask for his blessing. He gives it to me in Latin, his fingers pressed against my forehead as he makes the sign of the cross, before we bid each other farewell with a “God bless”. I feel we both want to belong to that “Church after battle” that Pope Francis has proclaimed needs healing.