Buy now from Amazon.co.ukBuy now from little, brownBuy now from WaterstonesBuy now from BookworldBuy now from booktopia

Buy now from Amazon.co.ukBuy now from little, brownBuy now from WaterstonesBuy now from BookworldBuy now from booktopia

America Magazine

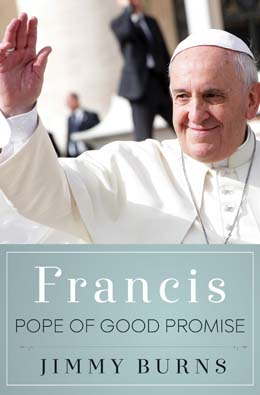

The fourth serious Francis biography, not contradicting but building on its predecessors, Jimmy Burns’s Francis, Pope of Good Promise (St. Martin’s Press, 432 pages, $28.99), will appear in September. Reading it was an always absorbing, sometimes thrilling, experience, largely because Burns, an Anglo-Spaniard Catholic with journalism experience in Buenos Aires and a contributor to CNN, BBC and The London Tablet, among other places, writes with a novelist’s grace and a historian’s perspective. He is always answering the question, “What else was going on when Bergoglio was here or there?” As a Jesuit provincial and as a bishop Burns’s constant moral question is, “How much injustice must Bergoglio witness and tolerate in order to avoid the retaliation of the state?” It took until May 1998 when he was 61 years old for Bergoglio to distance himself from the corrupt government of President Carlos Menen: “A few are sitting at the table and enriching themselves, the social fabric is being destroyed, the social divide is increasing, and everyone is suffering; as a result our society is on the road to confrontation,” he said.

Indeed, where have we heard those words before? Many like them have been used to describe the United States in recent years. They should be kept in mind as the U.S. church approaches not just Francis’ visit in the fall but also the Synod of Bishops on the family. Burns spends his final chapters interviewing lay and clerical leaders on the big issues that can make or break the church’s renewal: the Vatican bank scandal, the “long shadow of sexual abuse,” the role of women in the church’s future and a very sad interview with Hans Kung, who, suffering from a number of debilitating ailments, considers ending his own life. Whatever happens, Kung has corresponded with Pope Francis who, in long handwritten letters, has given him reason to hope.

Kirkus

Journalist Burns (La Roja: How Soccer Conquered Spain and How Soccer Conquered the World, 2012, etc.) admirably tackles a difficult subject but meets with mixed success. The author’s plan is evident: to introduce readers not only to Jorge Mario Bergoglio (now known as Pope Francis), but also to the setting in which he was raised, Argentina. What Burns presents, however, is largely a political history of modern Argentina, followed by a topical look at the young papacy. The result is unwieldy and untamed. Speaking often in the first person, Burns takes a guardedly positive view of the pope. As a young man, Bergoglio was deeply affected by populist President Juan Perón, and he remained a Peronist at heart throughout his life. Nevertheless, Bergoglio proved himself adept at navigating the terrifyingly choppy political waters of Argentina, surviving (figuratively and literally) a number of regimes and juntas through his years as a public figure. As head of the Jesuits in Argentina, and then as a bishop and later archbishop, Bergoglio found himself as an enforcer against leftist politics among his clergy while simultaneously working on behalf of the poor. Bergoglio is described variously as authoritarian and as pastoral, and Burns recounts a complex man shaped by the always volatile and sometimes-brutal realities of his nation. “While Pope Francis’s spirituality is not in doubt,” the author summarizes, “the life of Jorge Bergoglio, as Jesuit priest and bishop, was far from flawless, and deeply human in its vulnerability and complexity.” Without much of a transition, this imperfect character becomes pope, and the remainder of Burns’ work is dedicated to his papacy, seen from the view of various topics: poverty, economic scandal, gender, sexuality, etc. Francis comes across in each case as mildly positive as well as rather unpredictable.

A sprawling study that, though enlightening, takes readers on more of a journey than they may have bargained for.