Allen Lane) 1031 pages (£30.00)

Review for The Tablet submitted 16/11/2010

I approached this authorised history of the British secret service MI5 with a degree of scepticism. Is one dealing here with history researched by an independent historian or an apologia for a government organisation whose hundred years of existence has drawn its lifeblood from secrecy and varying economies of truth?

Christopher Andrew is a refreshingly unstuffy professor of Modern and Contemporary History at Cambridge, whose insights into the complex world of espionage and ability to convey them in comprehensible language has earned him, quite justifiably, huge international respect.

And yet by agreeing to the Official Secrets Act and becoming a member of MI5’s staff as a pre-condition for researching and writing In Defence of the Realm, he risks fuelling a reputation as a “court historian”- too close to the spies to be impartial- which his critics have held against him since his authorised collaboration with MI6 and soviet defectors on histories of the KGB.

Andrew has skilfully packed a great deal of information within the 1,000 page without letting the narrative become turgid or impenetrable at any point. From its early reference to the Secret Service Bureau-as it was called in 1909- and its offices rented from a retired private detective called Edward ‘Tricky” Drew to its concluding paragraph pointing-disconcertingly- to the unpredictable threat of Al Qaida, this is a cracking good read however much one might occasionally still question the impartiality of Andrew’s judgements.

M15 has come a long way since its early beginnings when it was staffed by two military officers who “had a yarn over the future and agreed to work together for the success of the cause.” It grew as an organisation in two world wars, the subsequent Cold War, and the ongoing war on terrorism. Andrew is enthusiastic about celebrating MI5’s achievements, while too often excusing its morally questionable activities and operational failings. He uses up too much space, in challenging the conspiracy theories that he believes have unfairly damaged MI5’s reputation, while not acknowledging generously enough much diligent investigative journalistic probing hitherto into the secret world.

Historical perspective-and availability of additional sources- makes the first fourty years of MI5 the more convincing part of this book, with the overwhelming evidence firmly showing how British spies comprehensively defeated the counterpart operations of Kaiser Wilhelm 11 and Hitler.

MI5 senior officers shared concerns about the perils of appeasement under Chamberlain, before contributing to the eventual defeat of the Nazi war machine with an extraordinary strategy of deceptions carried out by a colourful cast of disreputable double agents from the politically ambiguous Spanish Civil war veteran Juan Pujol ‘Garbo’ to the ex-con Eddie Chapman alias Agent Zig Zag.

By contrast MI5 was slow off the mark in assessing the broader impact of the Bolshevik Revolution outside Russia, with Andrew judging that that not until the mass expulsion of KGB and GRU (Soviet military intelligence) officers from the UK in 1971 did the UK gain the upper hand.

The so-called Cambridge Five spy ring -Philby, Burgess, Blunt, Maclean, and Cairncross-was one of the biggest identified blunders of UK intelligence history although Andrew struggles to present a convincing case against those who continue to believe that the soviet penetration was even more widespread.

We will probably never know whether some senior MI5 officers were as innocent of treachery as secret internal enquiries belatedly found them-but what is is clear just from the information that this book contains is that several would have been sacked in any other organisation for sheer incompetence.

When MI5 identified enemy agents or sympathisers and prepared files on them, it did so often on information provided by double-agents or defectors, a species Andrew rates as credible witnesses. By contrast the author too easily describes as rogue elements within MI5 those who plotted against Harold Wilson, after the service had allowed a secret file to be built up on the prime-minister.

Gripped as I was, and mostly in awe of this brave exercise in authorised intelligence history, I still found myself in the end questioning the credibility of some of the information, much of it selectively extracted from within the inclusive world of smokes and mirrors that the spies inhabit, where nothing is quite what it seems, and the distortion of the truth is all too often an essential tool of the trade. And I don’t blame Andrew for that, but the spies. ENDS

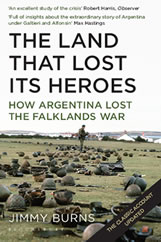

Note on the reviewer: Jimmy Burns’s new book Papa Spy: Love Faith & Betrayal in Wartime Spain is published by Bloomsbury.