Published by The Financial Times March 13 2010

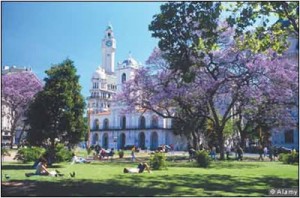

In the Plaza de Mayo, Buenos Aires, around the central pyramid that commemorates the overthrow of colonial Spain, a neat circle of painted white bandannas marks the spot where Las Madres de Mayo – some of the bravest women in the world – protested in the last decades of the 20th century against Argentina’s bloody military junta.

When I was in the square earlier this year the only protest was, ironically enough, that of a makeshift camping site set up by Malvinas, or Falkland Islands war veterans, who claimed to be more concerned by the unemployment benefits their own government had failed to pay them than they were about any newspaper reports of oil exploration by the piratas ingleses. Near them a group of children danced in the fountains, as if this were Rome, and a woman sold some flowers. It was as if a war that should never had happened had been consigned to history.

Just how much Buenos Aires has changed became apparent one weekend soon after my arrival. I recalled my early Buenos Aires days, when Las Madres de Mayo – female relatives of “the disappeared” – had conducted ritual protests in memory of their loved ones, who had been kidnapped and killed by the military regime. It was in April 1982 at the Plaza de Mayo, too, that Argentines had gathered in their thousands to celebrate the junta’s invasion of the UK-controlled but disputed Falkland Islands, just weeks after my posting to Argentina for the FT.

Now, a couple of decades later, I found myself following a group of Brazilian women tourists through the front gates of the presidential Casa Rosada. It seemed only yesterday that I had watched protesters being beaten to death a few steps from here before finding myself frisked and detained for alleged spying activities by heavily armed police. On this visit, however, we were welcomed by a smiling palace guard, or granadero, dressed in 19th-century uniform, declaring himself a multilinguist, said that he was our guide for the morning. The Brazilians wanted to have their pictures taken with him dancing an impromptu samba, while an American lady asked: “Is this where Evita sang ‘Don’t Cry for Me Argentina’?” Our guide was tolerant. He informed us that, though it was Madonna who had sung the song, it was, indeed, here that Eva had lived, as had her husband General Perón, who would soon be immortalised with a large statue near to the palace.

Two large halls housed photographic exhibitions: one showed a succession of Argentine women who had stood up against tyranny of one form or another. These icons of the persecuted and downtrodden seemed at odds with the luxury of the palace, home during the week to elected president Cristina Kirchner – a populist whose passion for speaking to crowds has more than a touch of Evita about it.

Much of the palace was as the military had left it. There was a chapel to the Virgin where the junta had prayed, convinced that God was on the side of repression. Nearby, a hand-carved, wood-panelled lift connected two floors decorated with chandeliers, mahogany furniture and a plethora of ivory, silver and gold artefacts.

Up a marble staircase and through Renaissance-style salons, I followed the guide out on to the main balcony overlooking the plaza and, in blazing sunshine, savoured the moment. I stood on the same spot where the defining moments of Argentina’s history had been played out before the crowd below – Evita giving her final speech before her death from cancer, Galtieri insisting that Mrs Thatcher had been militarily defeated, Diego Maradona holding up the 1986 football World Cup.

The 15-odd blocks of the San Telmo quarter are still for walking and discovering. I stumbled on a superb ice-cream parlour, a shoemaker who works marvels with leather, and countless bars and cafés where you can as comfortably eat breakfast as drown some soothing draft beer, while watching the world go by.

The military has been forced to retreat from whole areas they once occupied: the modernised docklands of Puerto Madero, for instance, are now the setting for riverside restaurants, hotels and luxury apartments and a stunning footbridge designed by Ricardo Calatrava. Along the road, some of the more traditional super-rich still inhabit La Recoleta, the super-elegant quarter in the style of Paris and Madrid that filled the writer VS Naipaul with such disgust so many years ago.

The neighbourhood these days struggles to keep its clientele amid a fear of crime. Residents claim that dangerous muggers have taken to hiding at night in the tentacles of Recoleta Park’s magnificent old ombu tree, a native evergreen, but elderly tourists still crowd the quarter’s sophisticated outdoor cafés in daytime. It’s an area that Naipaul found the epitome of Buenos Aires at its worst – pretentious and amoral. It still is, and some people still love it.

But the city elsewhere has been opening up, renewing itself. The middle-classes have been moving further north. The Palermo area has tastefully designed new apartment blocks and shops blending with the old. Its tree-lined cobbled streets have been restored, and once abandoned buildings gentrified. It is popular at night with a young well-heeled crowd that keeps talking into the early hours of the morning, when not setting off to dance somewhere.

Some of the new restaurants and boutiques that have opened in the barrios of Palermo Soho and Palermo Hollywood struck me as being as imitative as their names: I could have been in New York rather than South America. So instead I made my way to Las Cañitas, a less-hyped neighbourhood with its Argentine “village” pastimes of pavement chat and timeless lingering, where I atepampas-reared steak in a small restaurant.

My most culturally interesting evening came with the invitation from an Argentine girlfriend to the Canning, an old dance hall where she and a crowd of locals and foreigners danced tango. Since her divorce, she explained, she had become addicted to La Milonga – as the tango night is called locally. She owned up to enjoying the frisson of making eye contact with a stranger and being led to the dance floor, finding herself firmly clasped, and knowing that he had the expertise to guide her. Away from the tourist haunts, this genuine tango hall is not unlike a somewhat theatrical equivalent of a singles club, where city loners find temporary comfort or escape in the artifice of the tango.

And yet the traditional male dominance that seemed to be on display – my old friend, her eyes shut, allowing her partner to lead her across the dance floor – is deceptive. My friend is not the only woman who regards these tango nights as a kind of affirmation, as she makes her own decisions about who to dance with and what to do with him afterwards. Evita would have approved.

A new edition of Jimmy Burns’s book ‘The Hand of God: The Life of Diego Maradona’ is published in April (Bloomsbury)

Argentina’s bicentenary celebrations this year will include the reopening of the iconic opera house the Teatro Colón, the highlight of a varied programme of cultural activities.Museums, Maradona and the inevitable Evita

Visit the Museo de Arte Decorativo (www.mnad.org.ar), in the elegant Errázuriz palace, and the permament collections at the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano . You can walk among the dead at the Cemetery of La Recoleta (www.recoleta cemetery.com), extravagant home to hundreds of illustrious corpses, including Evita Perón’s.

Buenos Aires is not short of boutique hotels. Home Hotel (www.homebuenosaires.com) in Palermo district is a good place to chill in some style. It has an infinity pool, a holistic spa and good cocktails. Also very reasonable is the Art Hotel (www.arthotel.com.ar) near Recoleta.

Galerias Pacifico on Cordoba Avenue and Florida Street is one of the most stylish and beautifully designed of the downtown shopping malls. Check out the leather goods. For the more adventurous, San Telmo district is where you will find delicious ice-cream, curious bric-a-brac and quirky artisan shoeshops (my favourite is on Defensa and Brazil).

This is not a city for vegetarians. Argentine meat is the best in the world. You will find excellent steaks at Jackie O (Palermo) and El Mirasol (Puerto Madero). For the less carnivorous, try the fish and pasta at Oviedo (Barrio Norte) For breakfast or tea, I’d suggest the Café Richmond (Calle Florida), where Graham Greene set a scene of The Honorary Consul.

Leave consumerism behind and take a walk or a jog in the Reserva Ecológica Costanera Sur, the peaceful ecological park a stone’s throw from the modernised docklands.

La Bombonera stadium and museum are a must for football fans in the year that Diego Maradona will make a make or break appearance, as national team coach, in the World Cup in South Africa.

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2010.