How should we remember war ?

As a new virtual museum tells the story of the Spanish Civil War, Jimmy Burns looks at the place of memory in a seismic conflict (Published in The Tablet www.thetablet.co,uk 29/October/2022)

Spain limped into the third decade of the 20th century fractured “with one half of her being, for the other half lingered with El Cid and the conquistadores” .As Jan Morris went on to also note in The Presence of Spain,(published in 1964) she was “a mess of a country”, tortured by conflicting ideologies and dogmas. And in 1936, “centuries of failure, schism , and frustration gave birth to that ultimate despair, the Spanish Civil War.”

For the late historian Hugh Thomas, author of the first major account in any language of the Spanish Civil War, outside Spain (published in 1961) , the conflict was “the Spanish share in the tragic European breakdown of the twentieth century, and the sense of optimism ,that had lasted since the Renaissance, was shattered.”

Against this background , the recent launch of the first ever Virtual Museum of the Spanish Civil War (www.vscw.ca) is a bold initiative in the digital age, aimed at bringing a central event of history to a wider audience in a way that – as one of the project’s architects Antonio Cazorla-Sanchez puts it- “connects islands of memory in public history…connecting them to create a continent of knowledge.”

The museum, 10 years in the making , is the result of a collaborative investigation by a seven-person team of North American and European academics . A collectively signed article published recently in the leading Spanish newspaper El Pais, states: “We have been moved by an evident reality which is not always perceived: that in Spain there are very few history museums…and when it comes to the memory of the conflict, there are too many memories that have not found a place and too many places without memory”.

From its opening, striking image of a distraught woman in black crying over the bullet ridden body of a loved one- so resonant of current conflicts where civilians, often innocent bystanders, fall victims to armed interventions, suppression, and deepening unresolved propaganda and prejudice – I found myself immersed in an experience that is as instructive as it is moving.

We are reminded that although the Spanish Civil War came to involve foreign powers in a prelude to the Second Word War, its origins were endemic to Spain. The military uprising was ushered in by its plotters as a great crusade to safeguard the nation’s Christian heritage, with General Franco as one of the key commanders. It counted on military assistance from Hitler and Mussolini and was supported from the outset by the institutional Catholic Church, civilian faithful, including landowners and right-wing politicians .

The republican state that had replaced the failing monarchy of King Alfonso X111 in 1931 came to be supported by Stalin’s Russia, a range of foreign Marxists and romantic volunteers with the International Brigades, and Spanish socialists, Communists and anarchist ideologues who stirred up a revolutionary resistance by peasants and workers.

The military outcome of the civil war was also influenced by the policy of non-intervention, initiated by France and the Great Britain, with an agreement not to sell arms or material to either side signed by every European state except for the already neutral Switzerland.

Non-intervention in Spain was a “charade”, as Germany and Italy did not interrupt their support for the military rebels and non-intervention approved by Stanley Baldwin’s government was part of the British and also French policy of appeasement.

The museum site also states that Russia’s military assistance to the Republic was far outweighed by that offered by the German Nazis and the Italian fascists .It ignores the fact that by the mid 1930’s, far from a benevolent agent on the side of democracy , Stalin’s “terror” purges were already eliminating thousands of individuals deemed dangerous to the Soviet state , including Spaniards, as George Orwell would remind his readers.

But the museum is right in stating that World War 11 began with the German invasion of Poland on September 11, 1939, five months after Franco had proclaimed victory in the Spanish Civil War. The result of the defeat of the Republic was a “brutally repressive ,anti-democratic and fascist regime that would survive until 1977 two years after Franco’s death”.

While the museum’s text has some disputable omissions on the international context , its sections devoted to the confrontation between Spaniards are faultless , exposing the brutality on both sides, even if it could have made more of the looting by anarchists of Catholic churches and executions of clerics. This was a war that saw a new blurring of the boundary between combatants and non-combatants, with civilians constituting an increasing share of the casualties.

The museum site includes the tragic tale of Antonio Benaiges, a 31-year-old school teacher who encouraged his pupils in a small poverty-stricken village in the land-locked Castille & Leon region to imagine what the sea was like, and to draw it in their books. He promised to take them in the summer of 1936 to the Catalan coast so they could experience the sea for the first time. The trip never happened: the day after the military uprising the school was ransacked- Benaiges was tortured and executed by a group of right wing Falangists.

The museum reproduces a photograph of a a beautifully crafted book produced by the teacher and his pupils entitled The Sea , as seen by some children who have never seen it.

Iconography discovered by researchers includes a shattered devotional ceramic of the Virgin Mary and small crucifixes belonging to those killed or executed on both sides . As the narrative says: “The same object, then, means very different things on different sides: a political cause for the pro-Franco traditionalist Carlist requetés, an intimate and personal belief among Republic prisoners…after all, …there are no atheists in the trenches.”

The museum has been conceived by non-partisan professional Spaniards living abroad and their non-Spanish colleagues as part of a developing participatory project with a focus on digital as well as presentational outreach, engagement, and discernment. But though the Spanish Civil War remains a less contentious subject than it once was, the museum’s well-intentioned mission nonetheless faces political obstacles.

The museum went ‘live’ on the internet just days ahead of the Spanish parliament’s approval of the socialist-led government’s Democratic Memory law – supported by its Marxist minority partners Podemos and Basque and Catalan nationalists, but opposed by centrist and right-wing parties.

The law will help , so its backers claim, “settle Spanish democracy’s debt to its past” , and aims to build on a controversial 2007 act brought in by a previous socialist government which led to remaining statues of Franco being toppled and his body reburied in a less ostentatious cemetery.

Those opposed to the new Memory law and threatening to scrap it, if they return to power in a general election next year, include the main opposition party the Partido Popular. It claims the Left are rewriting the history of the civil war and undermining a consensual political pact after the death of Franco that aimed to draw a line with the past and focus on the future.

For now, it remains to be seen how a virtual museum of the Spanish Civil War can safely help navigate Spain’s binary politics and reach out to a new , younger generation, less scarred by, and perhaps better prepared to embrace, a less partisan and ideological version of the past.

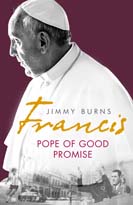

*Author & journalist Jimmy Burns was born in Madrid. His Spanish mother the late Mabel Marañón , along with her parents and sisters, was forced to leave Spain during the Spanish Civil War.She later married the Catholic publisher Tom Burns who was editor of The Tablet (1967-82). Jimmy chairs The British Spanish Society www.britishspanishsociety.org